Teaching Greatness, or Customer Satisfaction?

As a public, teaching-focused university, students are at the centre of MacEwan’s mission. Faculty certainly get paid—though far less than their peers at other universities. But they do not enter their profession to get rich. Instead, faculty are motivated by a passion to inspire and encourage, to guide, challenge, and inform future generations. And while students pay tuition—far too much, it often seems—they are not customers. We do not serve them fries or sell them widgets: we provide an education. Faculty care deeply about effective pedagogy. But how do we measure “teaching greatness”?

There are many options. Teaching dossiers are an effective way to showcase teaching styles and pedagogical methods. Peer evaluations, whether from classroom observations or assessments of curriculum design and course materials, can be highly effective measures. Student feedback also offers useful insights into student perspectives. Indeed, the vast majority of GMUFA members regard student input as crucial to pedagogical and professional growth. Student input on decisions like the pacing of material, user-friendliness of an online course, and value of study guides can feed into the iterative improvements and decisions faculty make about the design and delivery of their courses. On the other hand, a mounting body of research indicates that university-administered student course evaluations are biased, unfair, and ultimately ineffective measures of teaching effectiveness. While they provide insight into the student experience, they do not assess teaching proficiency or learning outcomes.

Following the switch from paper to online reports, voluntary response rates and student engagement have plummeted to unrepresentative lows. Quantitative scores discriminate against women and racial minorities, often in unconscious ways. And in a world where social media likes, online chatrooms, and anonymous comment boxes have degraded constructive discourse, student feedback surveys have transformed into spaces for the disaffected to vent or for admirers to gush (sometimes inappropriately). The results can even sometimes be ugly. Terms like “b*tch,” “c*nt,” and “f*cking idiot” occur in student reports received by MacEwan’s faculty. Some students complain about the pitch of female voices or the accents of professors. Other comments are overtly racist, sexist, homophobic, ableist, or ageist: too young, too old, too white, too Asian, “too flamboyant,” a “grey-haired white dude,” or “not very ladylike.” While other comments are more useless than abusive — “cute glasses!” or “nice hair!”— they hardly constitute constructive feedback. There is some comfort to know that such comments are far from universal, and in general students are highly satisfied with their professors! But a feedback system should be safe, informative, and professionally valuable for all involved.

While sometimes biased or unfair, one can nonetheless ask: do university-administered student feedback reports improve our teaching? The vast majority of MacEwan students, of course, are thoughtful and considerate and faculty value their perspectives. Yet students are not pedagogical experts. The average Yelp reviewer knows whether they liked the food at a restaurant, but they cannot evaluate its nutritional content, whether the duck was better braised or roasted, or whether maple-glazed parsnips were in fact the ideal accompaniment to the main. And doesn’t sugary food taste better anyway? Or perhaps well-plated food does? A patient, similarly, can comment on a doctor’s bedside manner, but they can hardly evaluate the physician’s medical expertise. A patient looking at a degree on the examination room wall from Tulane versus Vanderbilt is susceptible to availability bias at best, or all out ignorance at worst. Alas, MacEwan students certainly know whether they “liked” a professor or found a course easy or entertaining, but they are not well-equipped to assess learning or course outcomes.

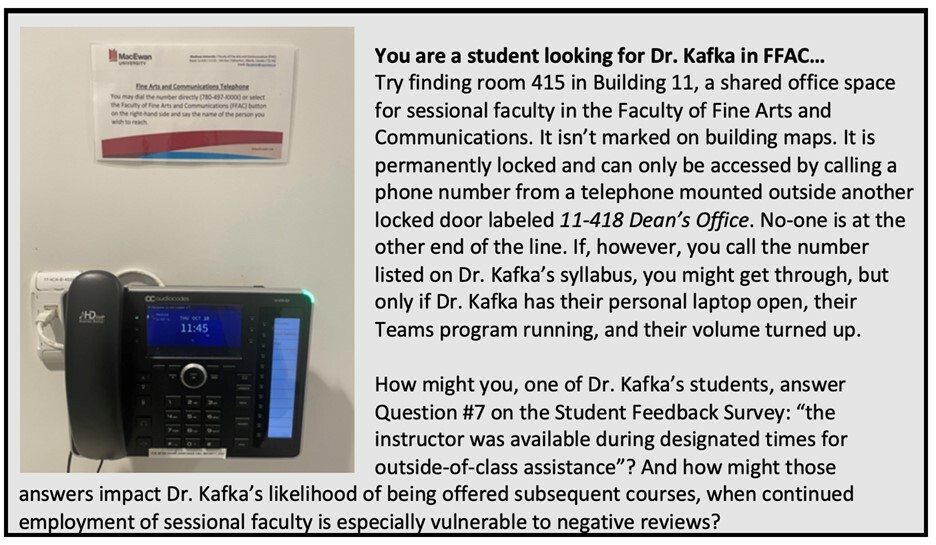

At worst, student feedback reports can be outright counterproductive. Fear of negative reviews places pressure on faculty to inflate grades and dilute expectations—measures that harm rather than facilitate teaching greatness. MacEwan faculty report avoiding controversial topics for fear of upsetting students. Others say they have continuously lowered the quality of their courses in order to improve their quantitative student feedback rankings. Indeed, one way to get high ratings is to make courses as easy as possible, and already the most common grade at MacEwan is an A-. Student feedback reports often reward lenience and popularity, but as barometers of teaching effectiveness, they are deeply flawed. At Toronto Metropolitan University an Ontario arbitrator concluded, in a precedent-setting 2018 case, that Student Feedback surveys should not be used in the evaluation of tenure, promotion, and other employment-related decisions. Yet at MacEwan, student feedback reports reign supreme, despite concerns like those described here, and that GMUFA members have regularly expressed.

The Board’s team has maintained that performance evaluations should necessarily consider student feedback surveys, and that university administrators are judicious consumers of information who read student feedback reports with an informed and critical eye. Further, they indicated that any tenure or promotion dossier that did not include student feedback reports would “raise a flag”, which was subsequently clarified as “would be viewed with curiosity”. Such comments, while multidimensionally interesting, suggest, at the least, that university-administered feedback reports are regarded as the default measure of teaching performance, and in many departments, they remain the principal means of assessing sessional teaching and determining future employment.

However immune those who sit in judgment may (or may not) be to human bias, faculty members impacted by harmful or discriminatory comments have no option to filter them out short of petitioning Human Resources on an individual case-by-case basis. Ironically, then, the process to remove derogatory, unhelpful, or unfounded comments requires affected faculty to spend even more time “experiencing” them as they draft emails, make their case, and follow up to verify their removal from the student evaluation record. Since discriminatory comments place an unfair burden on particular faculty demographics, they are a serious equity issue. They also constitute discrimination and harassment under the Canadian Human Rights code.

What is to be done? As an institution, we need to decide what we want to be. Do we want to be a degree mill, churning out as many satisfied customers as possible to facilitate unprecedented growth? Do we want to entertain our students and give them easy A’s? Or do we want to deliver a high-quality education that engages intensively with students, fosters critical thinking, and challenges them by taking them out of their comfort zone? Do we want to give them the adaptive education they will need to thrive in the twenty-first century? Or are we just servicing happy consumers in search of 5-star reviews? The answers here matter a lot to how GMUFA members plan their work and investment going forward. And surely, the answers matter to the new members MacEwan hopes to recruit.

If we value our role as educators, then it is essential to place pedagogical experts—that is, MacEwan’s faculty—at the centre of these decisions. Indeed, faculty care deeply about their vocation, and they are naturally drawn to opportunities for continued development of their teaching and professional practice. But the current system is stagnant, the opposite of innovative, and designed for scrutiny and reporting rather than professional development and growth. Changing the system requires, to some extent, a change in our culture of governance. GFC owns the student course feedback instrument and its renewal or revision, and GFC members have the capacity to squarely place this long overdue work on the Council’s workplan. The Collective Agreement sits apart from academic governance, and also offers avenues to address longstanding concerns raised by members.

GMUFA’s second significant proposal tabled new language revising Article 11: Evaluation of Teaching and Scholarly Activity. Key modifications include:

- Clarifying faculty responsibility to make their case in each area of workload, including reflections and supporting evidence.

- Additional metrics, like offering faculty members the opportunity to collect their own feedback using sound and evidence-based practices, and soliciting feedback tailored to specific pedagogical needs.

- The provision that written explanations be provided when a member is evaluated based on information beyond what they provide in their dossiers or performance reports. In other words, administrators, like faculty, need to show their work—that’s good pedagogical practice, one that embraces the spirit of initiatives of Open Science!

- Additional revisions to Article 11 add categories of evidence that members regard as important indices of scholarly engagement.

Above all, the goal is to provide faculty with greater autonomy in deciding how best to showcase their teaching effectiveness. Indeed, academics are skilled at putting forth well-reasoned cases with compelling evidence and supporting documentation. In many cases, that may mean reflecting upon the university-administered student surveys—there is no desire to eliminate them. But faculty who thoughtfully choose to exclude student feedback reports—particularly those filled with false, irrelevant, or derogatory content—in favour of other comparable evidence should not be subject to additional scrutiny.